Newspaper Article 10/01/2022

Commonality of interests have overshadowed Machiavellianism and this is what geo-economics is all about.

“I have a dream: cried Martin Luther King as he visualised a socially-knitted mosaic in the United States in the heydays of racism. So do I, and millions more of my contemporaries! Having eulogised peace and geostrategic cooperation for decades, the dawn of the synopsis of geo-economics is now close to our heart. Powerbrokers at the helm of affairs have ignited a ray of hope as they now firmly believe that Pakistan’s future and its progression rests in engaging with the region in terms of trade and travel, and this is how its tangibles can be mushroomed to the maximum.

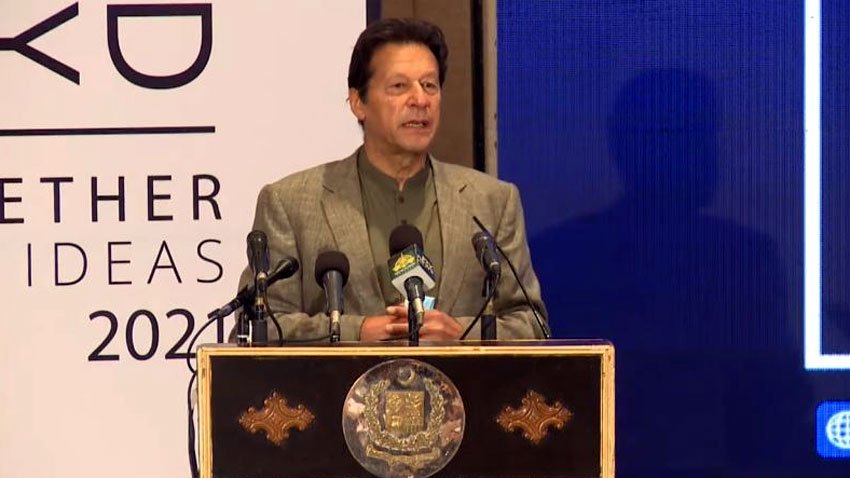

Forums such as the Margalla Dialogue and the Islamabad Security Dialogue are an extension of a thought process as to how Pakistan can recast itself at home, and reorient its geopolitical potentials to the collective betterment of three billion people in the region.

This phenomenon is no less than a renaissance in itself, as the world is changing around us. Pakistan has finally made a strategic choice by moving its entire policy paradigm from geopolitics to geo-economics. This is where a robust and an interactive future lies, especially as Pakistan is a theatre for the success of the Chinese multi billion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which connects three continents namely Asia, Europe and Africa.

Pakistan inevitably is an artery of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, with an investment to the tune of more than $60 billion, making it equivalent to Europe’s Marshal Plan in the post-World War II era. This is so because Pakistan sits at the crossroads of Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran and India. Last but not the least, it shares the world’s most friendly border with an emerging superpower, China much more promising than the vitals of US and Canada.

To quote former US president John F. Kennedy, “geography has made us neighbours; history has made us friends; economics has made us partners and necessity has made us allies. Those who God has so joined together, let no man put asunder.” This forms the dictum of Margalla Dialogue-2.0, which held its second edition in Islamabad in December 2021, similar on the lines of intellectual amalgamations such as Neemrana, Ottawa, Chaophraya, Delhi Dialogue and many others, with the explicit intention to harvest the bounties of collectivity in a world of interdependent intra-state relations. The dignitaries who came down to Islamabad made a strong point that Pakistan is catching up and alive to adaptability. This is a vindication of its foreign policy.

The point that Islamabad is being heard, and its policy prescription is getting feedback, is a success story of sorts. To what extent it is able to translate its theory of geo-economics into a doctrine of practicality will largely depend on the pooling of synergies and like-mindedness of all the players. The dye, nonetheless, has been cast and there is no going back on it.

Three important factors now form Pakistan’s approach towards the region, and its interaction with the world at large.

One – Peace in Afghanistan. The newly-attained tranquility should progress into opening up of the landlocked state for the region. It goes without saying that Pakistan has paid the biggest price in the post-World War II by fighting the other’s war known as ‘war on terrorism’, and has lost around $100 billion of its economy as well as the precious loss of more than 80,000 men. This went as a fodder for staking claim in the upheavals right across its western frontiers.

No one can thus say that Pakistan has meddled in Afghanistan for ulterior motives. In fact, it has been a victim of realpolitik as the United States played foul and then decamped from the Southwest Asian state. Now having attained a sigh of relief, as Afghanistan returns to normalcy, with the setting in of the Taliban government, the bounties of togetherness are in need of being shared.

This is why Pakistan is so proactive in finding a permanent and perpetual solution to the nation-building woes in the strife-torn country. An estimate says 23 million people are at the verge of starvation in an ensuing chilly winter.

The co-hoisting of OIC Foreign Ministers Conference in Islamabad under the auspices of Saudi Arabia was an apt demonstration of sincerity, and the sense of collectivism in brokering serenity. Until and unless the brewing humanitarian crisis is taken care of, the usurped assets of Kabul worth $9.5billion are released and the new dispensation is left on its own to experiment with neo-governance, the dream of geo-economics in the region by tapping Afghan territory will remain in shambles.

Two – Pakistan is in the Chinese camp. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity over it. But this doesn’t mean that Islamabad has turned anti-Washington. It is not the case, and it couldn’t be. There are innumerable common denominators between Pakistan and the US, and the foremost is their defense and intelligence cooperation, which cannot be put on the backburner.

Even though the US has exited physically from Afghanistan, it is there to stay in terms of security cooperation and a harbinger of change. The Taliban too understand these dynamics and have made it clear that they shouldn’t be portrayed as anti-American. It is national interests that matter and not flimsy assumptions.

Yet, Pakistan’s establishment has made a strategic relocation, it is Beijing that it looks up to! Indeed, the chemistry of geography serves the purpose, too, in being aligned with China as it rises as the dominant power-broker worldwide. Thus, commonality of interests has overshadowed Machiavellianism and this is what geo-economics is all about.

Islamabad and Beijing share at least two common denominators: to keep India within its size and restrict the US bullying the region. The trade and human exchange that will flow from Central Asia deep down to Africa and beyond will remain the format of diligence, and sooner rather than later the US and western powers too will be a part of it.

Washington will be more than happy to solicit Pakistan’s positivity in dealing with China, as the largest foreign holder of US debt is China, which owns more than $1.24 trillion. Without cash tranches from China on Manhattan, the US economy will be shut. This is interdependence in an age of 5G as China flexes its muscles.

Three – India must respond. The balance-sheet of geo-economics success inadvertently rests with how New Delhi acts and reacts to the mushrooming Chinese influence in the region. Pakistan has made its options very clear by stating that it has no qualms in dealing with India, provided it rescinds its draconian measures in occupied Kashmir.

Pakistan’s civil and military leadership have gone to the extent of saying that it can wait a little longer to see the dispute of Kashmir resolved, and as a confidence building measure let bilateralism work out in other spheres of discord. This is statesmanship, and India must respond to it in all far-sightedness.

If France can relinquish Algeria at the zenith of its power; Hong Kong can return to China from British tutelage and if Portugal can give up Timor, why not India budge on Kashmir? The fascist-political mentality in India is acting as an impediment in realizing the denominator of interaction. But the science and merits of geo-economics will overcome such fissures.

British High Commissioner to Islamabad, Dr. Christian Turner believes that Pakistan could see a 30 percent rise in GDP if trade with India is opened. The volume of annual transactions could be well above $200 billion. What more could the downtrodden of both the countries ask for? Peace and prosperity are interlinked, and the trajectory is trust and trade.

As the theme of Margalla Dialogue illustrated, “Breaking Past, Entering Future,” the path has been chosen. It is the characters on the stage that are in need of justifying their role, and not merely playing to the gallery. This is how the dream of congeniality in South Asia could stand realized.

Note: This article appeared in Defence Journal, dated 10 January 2022.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are of the author and do not necessarily represent Institute’s policy.