Newspaper Article 24/08/2016

China’s rise and increasing activism in the world during the past two decades has generated an academic analysis of China’s stated goals, plan of actions and future ambitions. Specifically, the announcement of One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative by President Xi Jinping in 2013, brought about several responses.

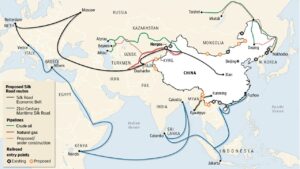

The initiative envisions jointly building Silk Road Economic Belt, 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The idea represents China’s new approach towards economic exchange and cooperation with adjacent regions. Thus, it is vital to understand its contents, principles and basic thinking from all dimensions and perspectives.

The Silk Road Economic Belt focuses on linking China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and West Asia; and connecting China with Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean. Under 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, one route is designed to go from China’s coast to Europe through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, and the other route from China’s coast through the South China Sea to the South Paci?c.

The initiative pursues revival of old Silk Road adhering to the principles of joint consultation, joint building and joint sharing. According to the economist Zheng Yongnian, “main objective of China’s going out action through the initiative of Belt and Road is not the Chinese government, but capital, and the government only plays a role of facilitating.” Significantly, the review of China’s of?cial statements and descriptions on the initiative reveals that all use the word ‘initiative’ instead of ‘strategy’. It might indicate that due to its open outlook, the initiative has received mutual consensus among member states on getting it implemented practically.

But the perception of initiative in US academia and public is complex. As the second largest global economy, China’s rapid advancement, increasing national resource and expansion of bilateral and multilateral ties, are a source of concern for the US.

However, Russia supports the initiative and issued China-Russia Joint Statement on a New Stage of Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination in 2014. China’s initiative has also received support from the UK, Germany, France, Italy and other developed countries that have decided to become founding members of the AIIB.

Within South Asia, only India has a way mixed reactions, by showing concerns along with willingness to actively participate in the initiative. To counter China’s initiative, India recently proposed the ‘Cotton Route’ so as to strengthen the diplomatic and economic relations between India and other countries of the Indian Ocean rim.

Other South Asian countries share common interests with China, in developing their economies and improving the livelihoods of their people. In 2014-15, President Xi Jinping visited key regional states and stressed on ‘creative cooperation model’, ‘joint building’ and ‘regional large scale cooperation’. South Asian states perceive that the joint building of the Belt and Road will not be a zero-sum game in which only one party would bene?t, rather it is a reciprocal and mutually bene?cial plan. The implementation of the initiative will effectively improve the infrastructures of the countries along the Belt and Road, and will promote facilitation of trade and investment, and thus improve industrial competitiveness of these countries.

In this context, it is vital to conduct analysis of the current status versus actual potential of level of economic openness and trade relations between South Asia and China. Some significant economic indicators mentioned by Yanfang Li in the “The Analysis of Trade and Investment between China and the regions/countries along the Maritime Silk Road,” are shared to develop an understanding.

South Asia covers an area of about 3.94 million sq. km with a population of more than 1,611 million (22.62% of the global population). The total amount of nominal GDP of these countries reached US $ 2.31 trillion and the per capita GDP stood at only US $ 1435. South Asia’s import and export made up 3.02% and 2.13 % of the global import and export trade volume. The Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) net in?ow totaled US $ 32.3 billion (2.23% of global FDI net inflow), and the FDI net out?ow totaled US $ 2 billion (0.14% of global FDI net inflow).

The openness of economy and trade of South Asian countries can be gauged from two dimensions i.e. Degree of Dependence upon Foreign Trade and Degree of Dependence upon Foreign Capital. South Asian countries are found to be highly dependent on both of these. Regarding the trade volume between China and South Asia, it reached US $ 93.6 billion and accounted for 2.25 % of China’s and only 9.68 % of South Asia’s total foreign trade volume.

Low achievements in terms of China-South Asia economic potential pertains to global slowdown in economic growth, decline in global trade and economic status, imbalances in regional development, and a gap in the development of economic and trade cooperation with China. Until the late 1990s, there was limited interaction between China and other small South Asian states due to natural barriers and India’s close cooperation with these states. Pakistan remained the only country that has a long history of close relationship with China.

Besides economic strengths and weaknesses, South Asian countries also differ in their political system, as well as religious and cultural affiliations. Given complex global political and economic relations, there is a need to establish pan-regional and cross-regional cooperation mechanism based on historical experiences. In this regard, the ASEAN “10 + 3” cooperation model provides a successful example. Through this model, China, Japan, and South Korea have established an in-depth cooperation with ASEAN. It would not be difficult to bring about similar mechanism between China and South Asia or SAARC states as most of them already welcome China’s regional involvement for both economic and political reasons.

The recent quest for resources and markets in South Asia, along with China’s willingness and ability to invest in infrastructure projects necessary to facilitate trade, has made China a desirable economic partner for other South Asian states. Pakistan and China have already taken the lead by starting the work on China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC, a project under OBOR, has increased economic significance, as it provides transit route for energy and other resources destined for China.

With the progress and prospects of CPEC, mutual consensus has emerged within South Asian states that China’s investments’ vision is designed to bring benefits not only to China, but will also provide income, jobs, and multifunctional infrastructure benefits to the recipient countries.

Seeing the regional states tilt towards economic engagement with China, Indian strategists propose that India should take measures to evade potential economic competitiveness with China without appearing to be anti-China while also encouraging US to remain actively engaged in the region without subordinating India’s interests to those of the US.

Contemporarily, in international cooperation, politics and economy are two closely related inter-dependent and mutually promoting aspects. Misinterpretation about the OBOR initiative would only cause some countries’ misunderstanding or reproach. Whereas for regional peace, there is a need to recognize that countries have more to gain through cooperation than from attempts to constrain one another.

Published by The SARCist (New Delhi, India)

Link of the Article: http://thesarcist.org/Opinion/146

Disclaimer: Views expressed are of the writer and are not necessarily reflective of IPRI policy.