By Ozer Khalid, senior consultant and foreign policy expert.

22 August 2021

Article one of a two-part series

Simmering Chinese-Indian border tensions heighten possibilities for an arms race in the Indo-Pacific and South Asian command theatres already on a nuclear knife’s edge, exacerbated by uncertainty in Afghanistan, turmoil a restive Occupied Kashmir, heated maritime escalation in the South and East China Sea(s) especially after AUKUS formation, the Quad’s hawkish naval posturing and a brewing U.S.-Chinese New Cold War over the Taiwan Straits. Shifting balance of power contests in South Asia must be analyzed through the lens of strategic influence in a wider context.

Raging and renewed Sino-Indian tensions in October 2021 are part of the geopolitical context within which Beijing now perceives New Delhi, as part of Washington’s camp, as an instigator seeking to destabilize Beijing. China observes India’s ferociousness in the South China Sea and retaliates with forays into the Indian Ocean and has been making open overtures to India’s neighbors and former allies.

China and India, compelled by burgeoning economies and soaring populations, are fiercely contesting regionally and internationally for energy, infrastructure, influence and natural resources.

In Delhi’s strategic calculus, China is a challenger to its power in the Indo-Pacific and Indian Ocean Region (IOR). The iron-clad Sino-Pakistan strategic nexus vis-à-vis India accelerates the implementation of transnational regional connectivity infrastructure projects like CPEC. Although currently Islamabad is responsible for the safety and security of CPEC, recent terrorist attacks in Balochistan and especially Dasu imply that closer security collaboration between Pakistan and China is in the offing, further aggravating geosecurity realities for India.

Pakistan is already the biggest importer of Chinese military equipment, especially high-end JF-17 fighter jets, battle tanks like the VT-4 Tank, and the Cai Hong 4 (CH-4) unmanned aerial vehicles developed by CASC. Pakistan also indigenously manufactured armed UAV`s like Burraq.

India lost geopolitical gravitas in Afghanistan after the Taliban take-over. Delhi desperately still funds a former Afghan government exiled in Tajikistan. The reduced strategic importance of the Chabahar Port between India and Iran and the rise of Pakistan`s Gwadar Port geostrategically checkmates Delhi.

Afghanistan is one of many land-locked Central Asian states reaping the benefits regional geo-economics and Chinese-investments from Pakistan`s Gwadar Port in cross-border trade. In 2020, Afghanistan imported 43,000 tons of fertilizers via Gwadar port, enhancing agricultural development.

To Delhi`s dismay, the Taliban 2.0 offers a resounding endorsement for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Taliban yearns to be a part of, and rolls out the red carpet for China`s Belt and Road (BRI) initiative; the first project expected to be launched is the Peshawar-Kabul road linking.

Indian Chinese animosity prompts rapprochement between India and the U.S. Such rapprochement was exemplified by recent U.S.-Indian joint military training exercises titled Yudh Abhyas in Alaska from October 15 to 29, 2021. The military training increases combined interoperability and Corps level capabilities of the Indian and U.S. Armies, with specific Indo-Pacific defense objectives, involving tackling unconventional and hybrid threats and future contingencies.

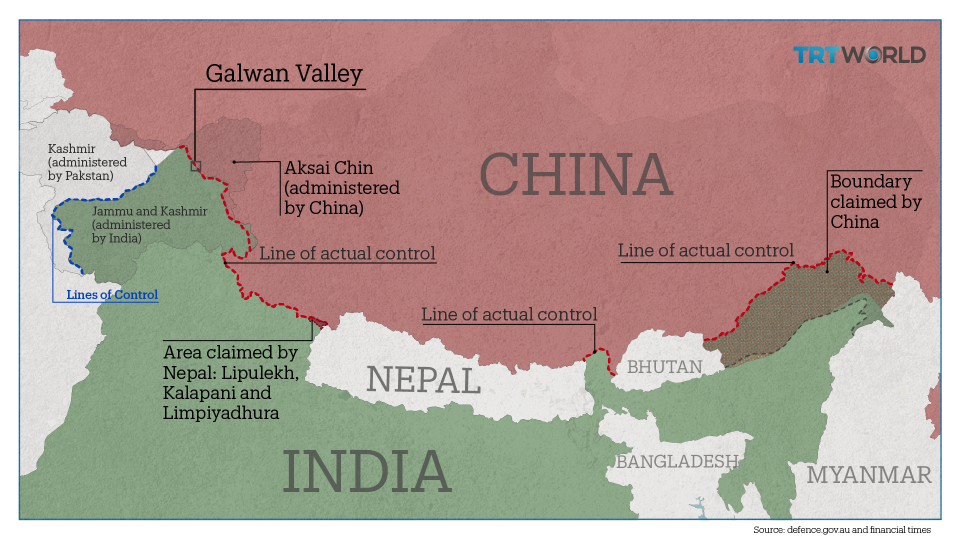

Major General Peter Andrysiak, former commander of U.S. Army Alaska stated that “The focus is mountainous, cold environments”. In other words, the U.S. is helping Indian troops specifically their 7th Battalion, Madras Regiment to train for high-altitude, cold-weather Himalayas terrain, to be better prepared in Ladakh and Galwan. Andrysiak told a discussion panel that the next training will be in the Himalayas.” An example of how Washington is openly taking sides in Indian-Chinese border contests.

India already nuclearised the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) with its submarine-launched ballistic missiles — the K-4, K-15, the Agni-4 and the Agni-5 — aimed at China, destabilizing the region’s complex strategic geometry.

India yearns to control all South Asian countries. It regards the region as its “backyard”. New Delhi is sensitive to any endeavor by smaller South Asian states seeking ties with other major powers. All small South Asian states and islands increasingly seek extrication from Delhi`s excessive leverage, including Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, Myanmar and Bangladesh. China and India jostle for spheres of influence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

New Delhi has sought to counter BRI by pursuing its own connectivity projects across the region—from a sub-regional energy hub comprising India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar to a natural gas pipeline linking Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

India is also regionally attempting to counterweigh China by investing and inking a US$700 million port deal with Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) to develop the Western Container Terminal of the Port of Colombo (POC) in the largest ever foreign investment in Sri Lanka’s port sector. The Adani Group enters a joint venture known as the Colombo West International Terminal where a new container jetty will be built with an annual capacity to handle 3.2 million containers. India also swayed Sri Lanka with a 300 MW LNG-based power plant at Kerawalapitiya and offered Colombo a $ 100 million Line of Credit for solar projects.

India is courting Kathmandu via the first cross-border petroleum products pipeline from Motihari in India to Amlekhgunj in Nepal expanding to Chitwan, with a pipeline linking Siliguri and Jhapa in Nepal.

Relations between Kathmandu and Delhi soured, however, when India deliberately misinterpreted the origin of the Kali River to claim Nepal’s lands in the Kalapani–Limpiyadhura region, including the Lipu Lekh.

India’s Home Ministry published an updated political map which showed the Kalapani region as Indian territory which Nepal’s government countered by publishing their own revised political and administrative map with the Kalapani-Limpiyadhura tract. The BJP’s over-zealous territorial ambition alienated Kathmandu, one of India’s historical allies but also set in motion the conditions for China’s expansion in the Himalayan nation.

Source: Legal Vidhi (2021)

Source: The Federal (2021)

All Indian soft power efforts in Nepal were overshadowed by China’s financial and technical assistance to Nepal worth 2.5 billion Nepali rupees (188 million U.S. dollars) in the 2020-21 involving infrastructure development,industrialization process, health and education development.

Beijing is upgrading Nepal’s Kodari Highway and restoring the bordering bridges at Kodari and Rasuwagadhi, upgrading the Syaprubensi- Rasuwagadhi Road and the Civil Service Hospital. The Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal (CAAN) DG Rajan Pokhrel confirmed that China’s CAMC Engineering Corporation would conduct construction works for the New Pokhara International Airport development.

Source: TRT (2020) India-China stand-off what might come next.

Maldives is another island becoming a battleground for Sino-Indian geopolitical influence. India’s influence over the Maldives waned after strongman Abdulla Yameen assumed power who swiftly secured Beijing’s backing. A 2017 China-Maldives free trade agreement ensued, as did Malé’s formal membership to China`s Belt and Road Initiative.

By 2018, Beijing had completed a huge runway upgrade whereby the Beijing Urban Construction Group inked a lucrative deal to expand the Velana International Airport in 2014, displacing India’s GMR which previously held the contract. In 2018 China also built the Sinamalé Bridge (the friendship bridge view hereunder) linking Malé to the island of Hulhumalé. These investments have accrued debts for the Maldives.

Source: India`s loss in the Maldives is China’s gain and it is showing, The Print (2018).

However, the tables turned again in 2018, when Mohamed Ibrahim Solih restored Maldivian ties with New Delhi. Solih launched an “India First” policy, scrapped the 2017 trade deal with Beijing. India authorized $1.4 billion to help the Maldives with loan paybacks and provided financial succor through six pacts for community development projects.

Delhi is currently building a $ 500 million Greater Malé Connectivity Project a 6.7 km bridge project connecting Malé with Gulhifalhu Port and Thilafushi industrial zone hailed as the largest ever infrastructure project in Maldives. Delhi is also bringing Maldives under it`s sphere of influence by building a 100 bed Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital(IGMH) a Multi-Specialty cancer hospital, in Western Malé as well as an $800m 22,000-seat cricket stadium. The Airports Authority of India (AAI) also upgrades the Hanimadhoo airport in Northern Maldives.

India is also relying on Covid-19 vaccine diplomacy to try and reassert influence over Maldives by dispatching 100,000 Covishield vaccines.

All the above along with the resurgence of the Quad (Quadrilateral security dialogue) arrangement comprising of America, Australia, Japan and India, evaporates any existing goodwill between Beijing and Delhi. The Quad, carries the weight of its own internal contradictions, is overshadowed by AUKUS, remains a fledgling grouping of continually changes priorities, earlier aimed at tackling a raging Covid-19 which now totally reoriented towards “China containment”, emboldening and nudging Delhi onto a more belligerent posture.

Even after walking on egg-shells with Chinese PLA soldiers in mortal border clashes, Delhi, fearful of a two-front war with China and Pakistan, has still been half-heartedly tiptoeing toward a more offensive regional military posture.

A Biden administration, not letting the Indian Ocean slip away, nudges Delhi’s anti-China sentiments recently emboldened with diplomatic wind in its sails after inking a deal with the United Kingdom and Australia to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarines over the following eighteen months.

Beijing’s retort is an increasing military footprint in the region. China, as a defensive response, toughens its military stance in South and Central Asia and the Indo-Pacific region ever since the messily haphazard American withdrawal from Afghanistan. Taiwan’s territorial status increases in urgency. China flew J-16 jet fighters, H-6 strategic bombers and Y-8 submarine-spotting aircraft into the island’s air defense zone as U.S. special-operations unit covertly train Taiwanese troops for combat. These are efforts to shore up the island’s defenses vis-à-vis China.

China also leverages its “soft power” through regional and global Confucius Institutes, and consolidates its rising economic influential heft through regional forums such as ASEAN, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

At present, Delhi struggles to keep up with China’s loftier investment momentum in South Asia. Delhi is being outfoxed in its own backyard. China’s strategic assets in Gwadar, Hambantota, Chittagong, Taxgoran and Wakhan strengthen its sphere of influence and logistical reach and infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific theatre.

All territorial border disputes tend to be long-term and protracted raging on for decades. India and China’s disputes are no exception. Regional influence rivalries spill all over into Indian Ocean and South China Sea only to intensify in the coming months and years.

In an “ideal” world, both countries should have disengaged from the border hotspots, refrained from armed clashes and circumvented patrolling in “disputed areas” however, in realpolitik such demands will remain wishful thinking.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are of the author and do not necessarily represent the institute’s policy.