It is refreshing that the recent lunatic orders, which apparently came from the Bangladesh Cricket Board but had the blessing of the highest political office of the country, have been revoked. Edict was aimed at banning the domestic fans from carrying the flags of foreign countries in the stadiums during the ongoing World T20 Championship. Bangladesh invoked this law after Bangladeshi Cricket fans carried Pakistani flags during Pakistan’s matches with India and Australia. It reminds one of an earlier event when Pakistan won the thrilling final of the 2012 Asia Cup, also played in Bangladesh. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina stormed out of the stadium without applauding the winning team or giving away the winner’s trophy. Similar childish attitude seems to be on display these days.

Bangladesh’s political party, Awami League (AL), carries a legacy of trumping up anti-Pakistan frenzy for political expediency. When in government, it employs the entire State apparatus toward this end. Being the founding party of Bangladesh, it made a negative start by putting forward fictional figures about war atrocities. Instead of giving a healing touch to its people, many a times, AL deliberately reversed the near healing process by re-scratching the fading memories.

Right from the beginning, there has been a very powerful counter narrative to atrocities’ related official figures; interestingly it emerged from within Bangladesh as much as from the international community. Bangladesh’s public at large does not subscribe to the AL version of 1971 war. Frustration mounts when AL government bulldozes down its narrative as the only authentic version of history. This strategy helps the AL in two ways: justifies its policy of appeasement towards India; and provides it a handle over public sentiment, which it tries to exploit as political expediency, on as required basis. AL conveniently ignores the atrocities committed by ethnic Bengalis against non-Bengalis that lead to military operation on March 26, 1971; though heaps of literature is available on this count.

Right from the beginning, there has been a very powerful counter narrative to atrocities’ related official figures; interestingly it emerged from within Bangladesh as much as from the international community. Bangladesh’s public at large does not subscribe to the AL version of 1971 war. Frustration mounts when AL government bulldozes down its narrative as the only authentic version of history. This strategy helps the AL in two ways: justifies its policy of appeasement towards India; and provides it a handle over public sentiment, which it tries to exploit as political expediency, on as required basis. AL conveniently ignores the atrocities committed by ethnic Bengalis against non-Bengalis that lead to military operation on March 26, 1971; though heaps of literature is available on this count.

Latest step to malign Pakistan is an upcoming play in the UK being enacted by Komola Collective, a London-based theatre. Play is based on the AL version of atrocities committed by Pakistani troops during 1971 war. Theme of the play has already been refuted by independent analysts including those from Bengalis and Hindu communities. The play, which will premiere in London on April 9, is called “Birangona” — meaning “Brave Woman” or “War Heroine”. Perception has it that this activity is being heavily funded by Bangladesh and India.

Following madness as strategy, the Bangladesh ruling party is targeting those Bangladeshis, who were against the dismemberment of Pakistan. After targeting the Jamaat-e-Islami, and sentencing its leaders to death, Jamaat-e-Islami is now to stand trial, as an entity. In her February 4, 2014 address to the Bangladesh parliament, Sheikh Hasina declared that fresh investigations would be launched to ascertain whether Begum Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party was involved in smuggling 10 truckloads of arms with the help of ISI.

The so called International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) was set up in 2009. Ever since ICT has been under severe criticism— both from within and outside Bangladesh. By 2012, nine leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami, and two of the Bangladesh National Party, had been indicted and convicted. The Four-Party Alliance, including the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami, have several alleged war criminals among their top-ranking politicians. Bangladeshi opposition political parties have demanded the release of those held, claiming the arrests are politically motivated.

International community has persistently voiced concerns that these trials are neither transparent nor impartial. Human Rights Watch, which initially supported the establishment of the tribunal, has severely condemned it for issues of fairness and transparency, as well as reported harassment of lawyers and witnesses representing the accused. Kristine A. Huskey, writing for the NGO “Crimes of War”, has said that a ten-page letter was given to the prosecution which included various concerns. A Wikileaks cable in November 2010 said, “There is little doubt that hard-line elements within the ruling party believe that the time is right to crush Jamaat and other Islamic parties. Steven Kay, a British Queen’s Counsel and criminal attorney, has said: “The current system of war crimes trial and its law in Bangladesh does not include international concerns, required to ensure a fair, impartial and transparent trial.” The Turkish president Abdullah Gül sent a letter asking that clemency be shown to those accused of war crimes. The European Parliament has expressed its strong opposition against the use of the death penalty. Sam Zarifi of the International Commission of Jurists expressed concern that the flawed nature of trials conducted at the ICT could deepen the divisions in Bangladeshi society. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has said that the refusal by the government to grant bail violates Article 9 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

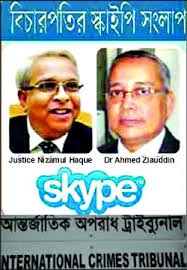

In December 2012, the Economist published contents of leaked communications between the then chief justice of the tribunal, Mohammed Nizamul Huq, and Ahmed Ziauddin, a Bangladeshi attorney in Brussels. After this, Huq resigned from the tribunal. He had been revealed to have had “prohibited contact” with the “prosecution, government officials, and an external adviser.” According to the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), the e-mails and Skype calls showed that Ziauddin was playing an important part in the proceedings, although he had no legal standing. The WSJ also said that the communications suggested that the Bangladeshi government was trying to secure a quick verdict, as Huq referred to pressure from a government official. In March 2013, the Economist again criticized the tribunal, mentioning government interference, restrictions on public discussion, not enough time allocated for the defense, the kidnapping of a defense witness and the judge resigning due to controversy over his neutrality.

After this, Huq resigned from the tribunal. He had been revealed to have had “prohibited contact” with the “prosecution, government officials, and an external adviser.” According to the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), the e-mails and Skype calls showed that Ziauddin was playing an important part in the proceedings, although he had no legal standing. The WSJ also said that the communications suggested that the Bangladeshi government was trying to secure a quick verdict, as Huq referred to pressure from a government official. In March 2013, the Economist again criticized the tribunal, mentioning government interference, restrictions on public discussion, not enough time allocated for the defense, the kidnapping of a defense witness and the judge resigning due to controversy over his neutrality.

Human Rights Watch and defence lawyers, acting for Ghulam Azam and Delawar Hossain Sayeedi, requested retrials for the two because of the controversy during their trials. Brad Adams of Human Rights Watch expressed concern that because of changes among all the judges in the course of the trial, none of the three judges in Sayeedi’s case would have heard the entirety of the testimony before reaching a verdict. On 28 February 2013, Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, the deputy of Jamaat, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. His defence lawyer had earlier complained that a witness who was supposed to testify for him was abducted from the gates of the courthouse on November 5, 2012, reportedly by police, and has not been heard from since. In May 2013, Bali was found in an Indian prison, and he alleged state abduction and that officials had told him that both he and Sayeedi would be killed.

Brad Adams, director of the Asia branch of Human Rights Watch, said in November 2012: “The trials against (…) the alleged war criminals are deeply problematic, riddled with questions about the independence and impartiality of the judges and fairness of the process”. Toby Cadman, an international law expert has also been highly critical of the ICT, saying of the international community “Expressing concern will not be enough. The international community should take quick action to stop the injustice being committed against Jamaat leaders.”

No one forced Bangladesh to abandon the war trials after independence. It was a well thought out decision by Sheikh Mujib to call it off. He was aware that his version of atrocities won’t stand a judicial scrutiny and would only make the society divisive and polarized. Sheikh Hasina needs to pick up cues from her father and act rationally. Pakistan bashing would neither bring good to her country nor the people of Bangladesh. She should let the people to people affection take its due course.

Carried by The Nation on March 31, 2014.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect IPRI policy.